Summary

Committed OKRs must be achievable by a cycle’s end. Resources and schedules should be adjusted to make sure they get done. Unlike committed OKRs, aspirational OKRs are achievable goals that set the bar further than a team’s ability to execute in a given quarter. They are carried forward until they are achieved.

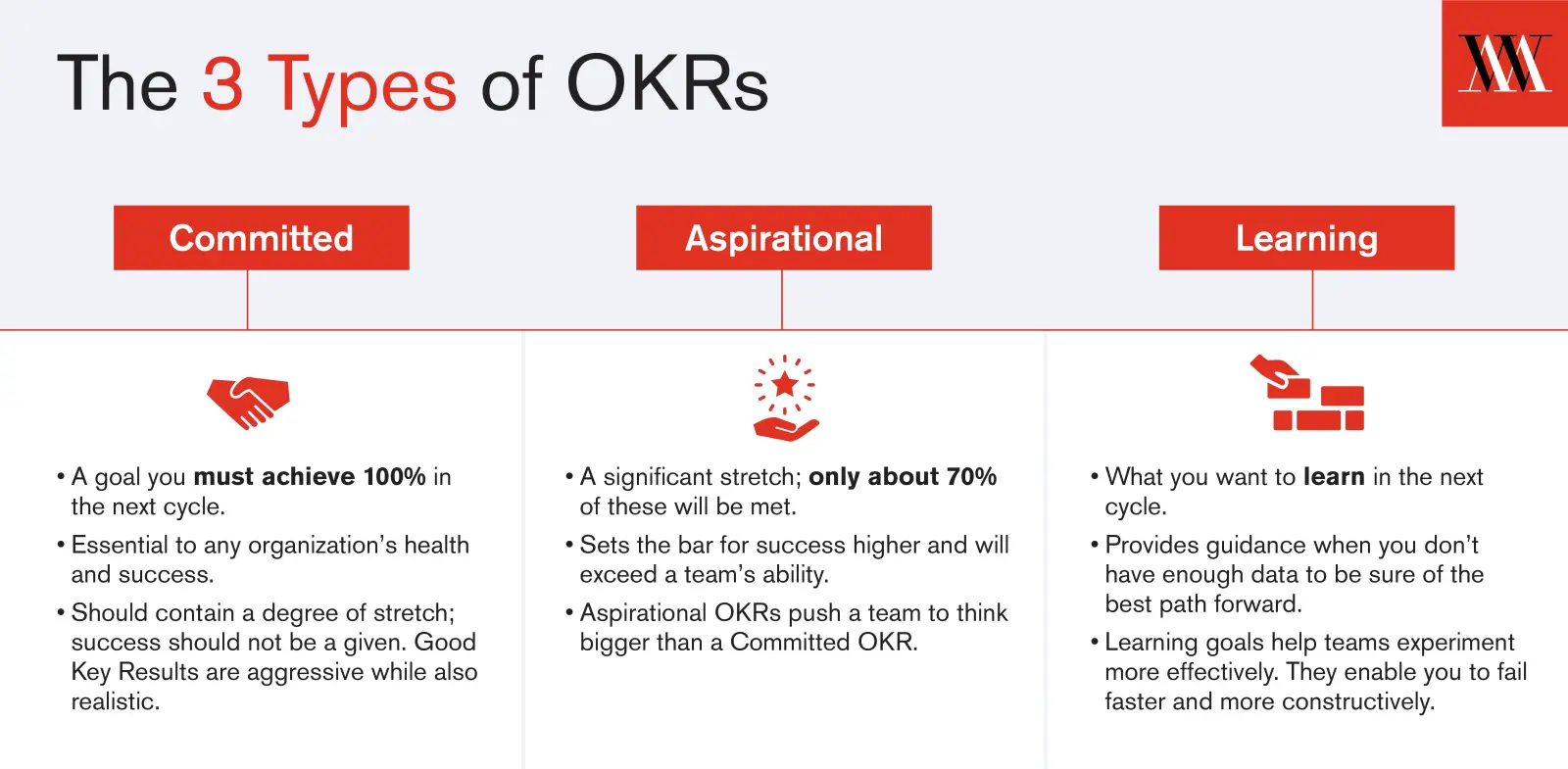

Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) are a tool to align everyone in your organization around your most important priorities. OKRs help answer two critical questions. The first: “Where do we want to go?” The second: “How will we know when we get there?” Depending on the answer, you may want to categorize your OKRs as one of three types: committed, aspirational or learning. Let’s explore differences between committed and aspirational OKRs in greater depth.

Are stretch goals, aspirational, and committed OKRs the same thing?

Stretch goals and OKRs have a lot in common, but there are a few meaningful differences:

- All OKRs are stretch goals, but OKRs are only used for an organization’s most important priorities. A stretch goal can be any goal that is beyond current capabilities.

- OKRs have two specific components: an Objective with a corresponding set of measurable Key Results.

- OKRs include regular check-ins to track progress and adapt to change. They form the basis of your most important conversations, meetings, and work plans.

A strong OKR will stretch your team’s capabilities. But how much to stretch depends on the organization, and sometimes the team using them. To avoid confusion, it may be helpful to know the difference between two common types of stretch goals: committed OKRs and aspirational OKRs.

A committed OKR is an ambitious goal that a team must achieve by the end of the cycle. A committed goal stretches the team, but is realistic to achieve. All metrics in the Key Results must be met in full and on time.

An aspirational OKR is a goal that sets the bar for success further out, and by design will exceed a team’s ability to execute in a given quarter. When they set such a high bar as to be seemingly impossible, they are called 10x goals, or “moonshots.” Even though most aspirational OKRs fail to be fully achieved, they exist to push a team to think bigger than a committed OKR. These aspirational OKRs should remain on a team’s OKR list until they are completed. As long as meaningful progress is achievable, falling short on an aspirational OKR is okay, even expected. As Google’s co-founder Larry Page says, “When you aim for the stars you may come up short, but still reach the moon.”

What is the difference between committed and aspirational OKRs?

Committed and aspirational goals reflect different attitudes about success. For example, winning the Super Bowl might be an appropriate aspirational stretch goal for a high-ranking league. However, they might also commit to losing fewer games than the previous season. Each goal affects how they recruit talent, the training they do, and the improvements they prioritize.

Aspirational OKRs are, by definition, beyond reach. Taking big risks and falling short is somewhat expected. But failure is celebrated as a valiant attempt to get closer to the finish line, rather than evidence of a team’s shortcomings.

Committed OKRs have less wiggle room for failure. Teams who cannot deliver on a committed OKR on time should escalate to management promptly, so they can work together to create solutions and alternatives in time to get back on track.

What are the advantages of committed vs. aspirational OKRs?

Reaching 100% of an aspirational OKR is rare. Aspirational goals often help teams make steady progress over time towards a seemingly impossible goal. Getting 70% of a Big Hairy Audacious Goal (BHAG) gets you much farther than just 10% of a mediocre goal.

When Andy Grove first introduced OKRs to Intel, only one type of OKR existed: aspirational. Intel was facing an existential threat to beat Motorola in the microprocessor market. The company failed to fully achieve most of their OKRs, but setting the bar so high forced everyone to think bigger and achieve more together. Eventually, OKRs helped Intel win the market, giving birth to Silicon Valley as we know it today.

Committed OKRs ensure teams focus on priorities where there is less room for failure. Google has used OKRs successfully since 1999. Although most of their goals are aspirational OKRs, they also recognize that some OKRs need to be completed by the cycle’s end. So they created a second category: committed OKRs. It helps them distinguish “must-do” goals from more idealistic ones.

Which is more effective - committed or aspirational OKRs?

Both committed and aspirational OKRs contribute to an organization’s health and success. Many organizations use a mix of committed and aspirational OKRs. Designating OKRs as committed or aspirational signals how much effort is expected of the team.

Use aspirational OKRs when you expect a goal to take several OKR cycles to complete. The Objective can stay the same from cycle to cycle, and carry forward any Key Results that aren’t fully met too. Eventually, when the OKR becomes within reach, try labeling it a committed OKR instead. It will signal that the goal should be complete by the end of the cycle.

How to grade committed vs. aspirational OKRs

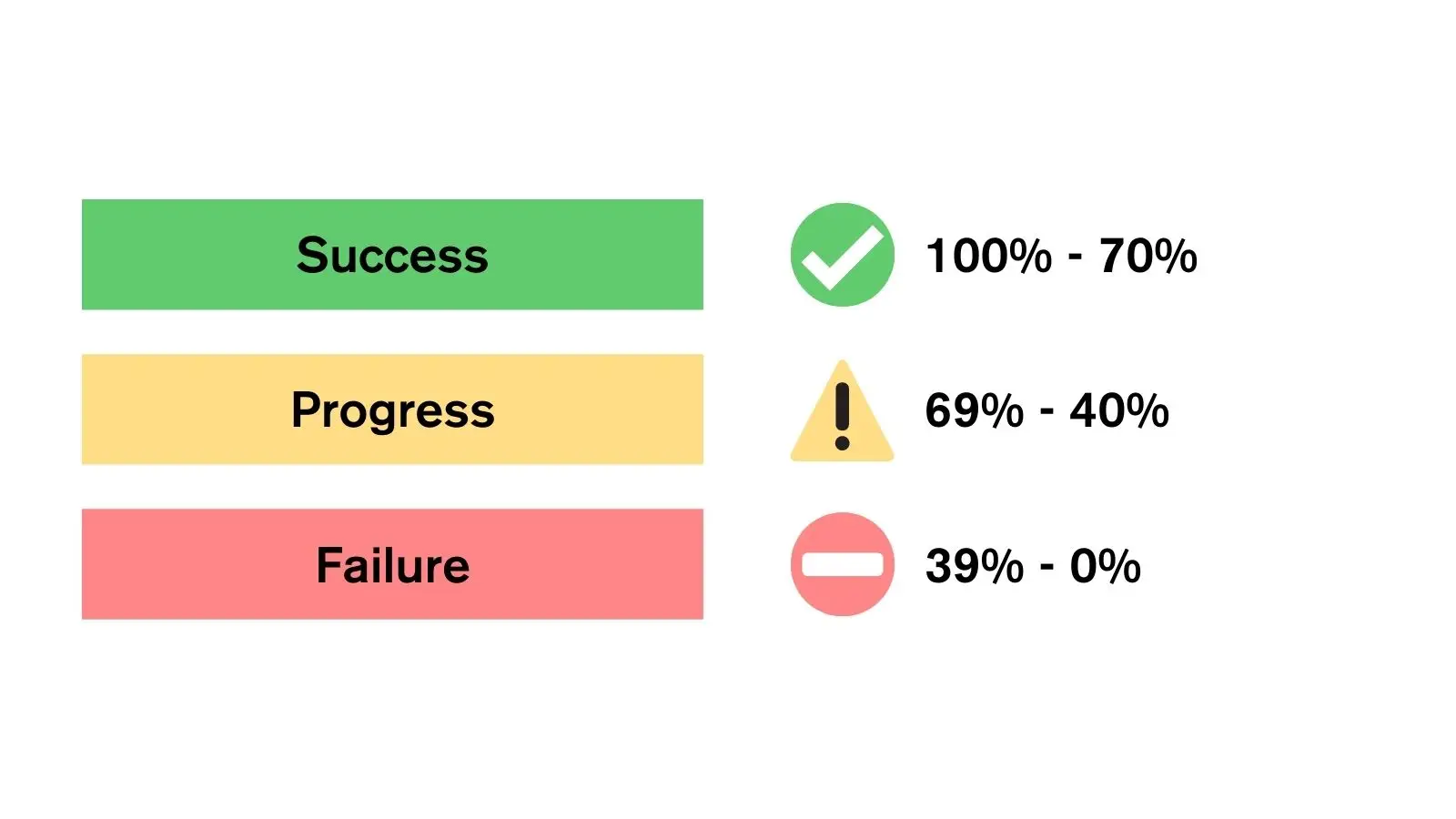

An OKR’s grade is simply the average of the scores of its Key Results. Grading brings home a key difference between committed and aspirational OKRs.

Committed OKRs must be achieved within the cycle. Grading is binary: pass or fail. An OKR is either achieved 100 percent (pass) or not (fail).

Aspirational OKRs are a little more nuanced. Google sets a lot of aspirational goals, and expects teams to achieve an average of 70 percent on its OKRs. They consider anything below 40 percent a failing grade, and anything between 40 and 70 percent as good progress, but not as far as they’d hoped:

How to avoid confusing committed with aspirational OKRs

- Label aspirational and committed OKRs clearly: It’s as simple as placing an “A” next to aspirational OKRs and a “C” next to committed OKRs in order to avoid confusion. Teams may underperform if they think a committed OKR is aspirational. If the team mistakes an aspirational OKR for a committed one, they may feel defeated — fearing for their jobs, or making them timid.

- Define success at the start of the OKR cycle: Let teams know what’s expected as early as possible. Waiting until the middle or end of an OKR cycle to decide or communicate is unfair — and risks wasting effort and frustrating the team.

- Set a high bar for labeling an OKR aspirational: It takes practice to develop good goal-setting muscle. At first, some aspirational goals will be too timid; some committed goals will be too ambitious. To help, ask your teams, “What do my customers really wish for?” An aspirational OKR should meet or exceed that wish. If the answer feels doable, it’s more likely a committed OKR.

- Committing to an OKR too soon: OKRs commit teams, time and attention to a specific direction. If it’s too early for you to know if your revenue model is sustainable, or if there’s product/market fit, avoid setting a committed or aspirational OKR just yet. Rather than setting a goal around what you are striving to accomplish, frame it around what you are trying to learn. Read more about learning OKRs, the third category of OKRs

It will help everyone in your organization to state clearly whether completing an OKR is an aspiration or a commitment. Your team deserves to know how to gauge and prioritize their efforts before they start organizing the work.

Where can I get more information?

Ready to learn more about OKRs? Get the basics of OKRs in our free OKRs 101 course for beginners.